THE WATCH STAFF

If a reminder is needed of Alaska’s strategic importance for the security of the Arctic and North America, U.S. Air Force Lt. Gen. David Krumm offers two helpful axioms:

- “It’s all about location, location, location.”

- “Tracers work both ways.”

One applies to business and real estate; the other references luminescent military ammunition — “tracers.”

Of the first axiom, Krumm, commander of the Alaska Region of the North American Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD) and Alaskan Command, said he can get to anywhere in the Northern Hemisphere from Alaska in less than nine hours. And just 55 miles of water or ice separate Alaska from the Russian coast at its nearest point.

“Alaska is what makes America an Arctic nation,” Krumm said.

“I’ve had people from (U.S. Indo-Pacific Command) come here … and I remind them that I can get to Seoul and I can get to Tokyo faster from here than they can from Hawaii,” Krumm said during a September 16 Arctic eTalk on U.S. Arctic security titled, “Defending the Northern Approaches.”

The Arctic eTalks are a monthly online forum co-hosted in part by U.S. Northern Command, its commander’s magazine, The Watch, and the Center for Arctic Security and Resilience.

Of the second axiom, Krumm said: “And what does that mean? That means not only do we have the ability to … deploy forces anywhere in the Northern Hemisphere very quickly (from) Alaska. It also means that an avenue of approach back to Alaska comes through the Arctic. … The closest point to threaten or put at risk North America is through Alaska as well.”

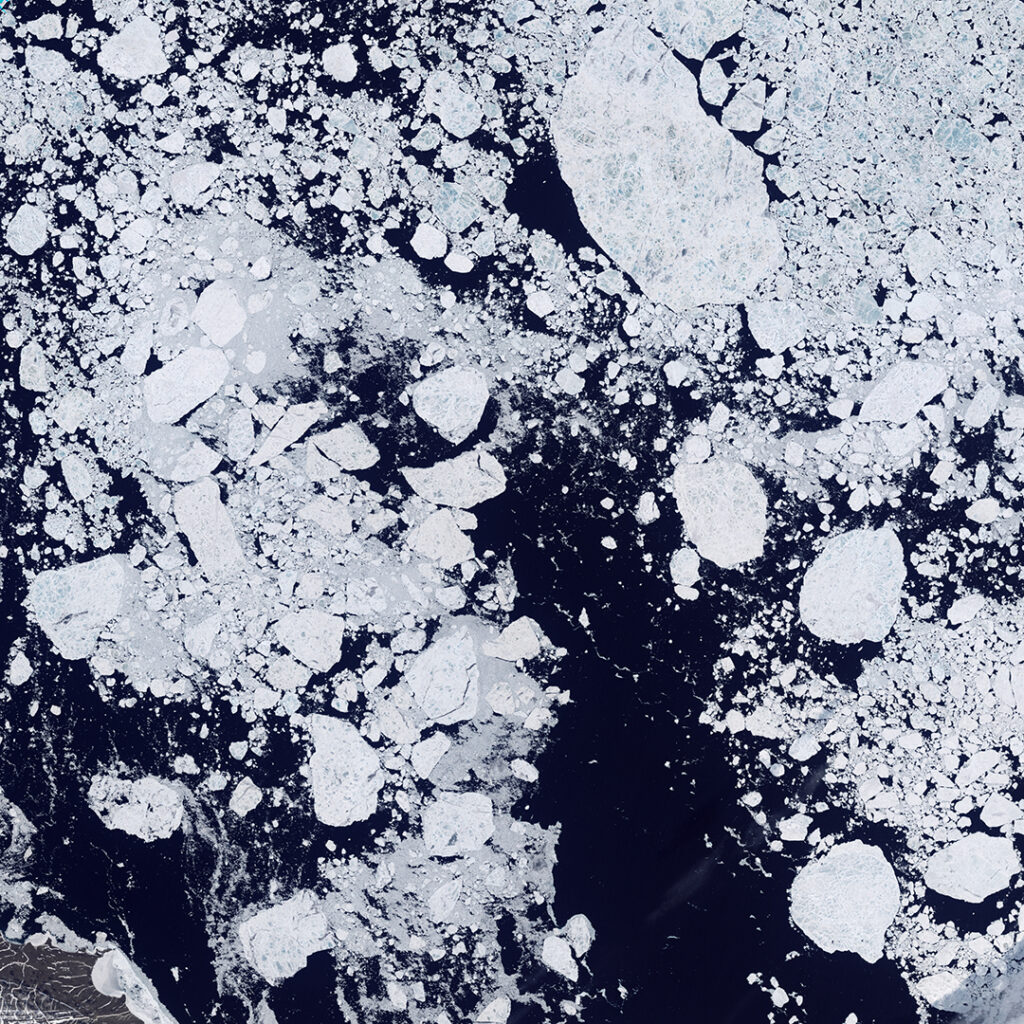

Those geographic factors have been amplified by climate change and the resulting reduction of Arctic sea ice, which has opened shipping lanes and increased maritime traffic. Krumm displayed satellite photos of the Arctic ice in 1979 and 2020 that showed the changes in stark relief. (Pictured: A satellite view shows Arctic sea ice in 2001.) The ice thaw has also led to greater access to natural resources such as oil and natural gas, minerals and fisheries.

“What’s happening is the Arctic is warming, now it’s not exact, but (at) about twice the rate of the rest of the world,” Krumm said, “and that is having profound changes in the environment up here.”

Another profound change: Even non-Arctic nations — China, for example — are looking at the region’s natural resources with envy.

Beyond the commercial and economic challenges, potential adversaries such as China and Arctic nation Russia are investing in missile technology that’s no longer constrained by a natural Arctic buffer. As a result, Krumm said, they are moving forces into the high Arctic for longer periods with plans for infrastructure that would allow them a year-round presence. Russia, for example, has the largest permanent military presence in the Arctic, according to a July 21, 2020, story from Department of Defense News.

So how best to defend North America and U.S. interests in the Arctic?

Krumm, in a September 15, 2021, column for the Defense Visual Information Distribution Service, wrote: “To do so means a resilient, persistent presence and the ability to operate from both main operating bases and more austere locations across Alaska. This is known as Agile Combat Employment (ACE).”

Krumm pointed out that an ACE example took place in May 2021 during the Operation Noble Defender exercise when U.S. Air Force F-22 Raptors were deployed to the tiny community of King Salmon, Alaska. The Air Force’s Arctic Strategy, released in 2020, lists four lines of effort that include vigilance, power projection, cooperation and preparation.

That cooperation includes U.S. allies, and Krumm said the relationship with one of them is paramount.

“The Alliance that we have, Canada, I think it’s unmatched,” he said of the U.S. partner in NORAD.

“I think Canada understands that information is important,” Krumm said. “We get that with domain awareness, we get that by having the right sensor network that’s connected and we’ve got to share it. … What I’d love to see is even more infrastructure placed along the Northern tier that we can integrate and work together.”

IMAGE CREDIT: NASA