A Chinese paramilitary police border guard trains in Heilongjiang province on the border with Russia. AFP/GETTY IMAGES

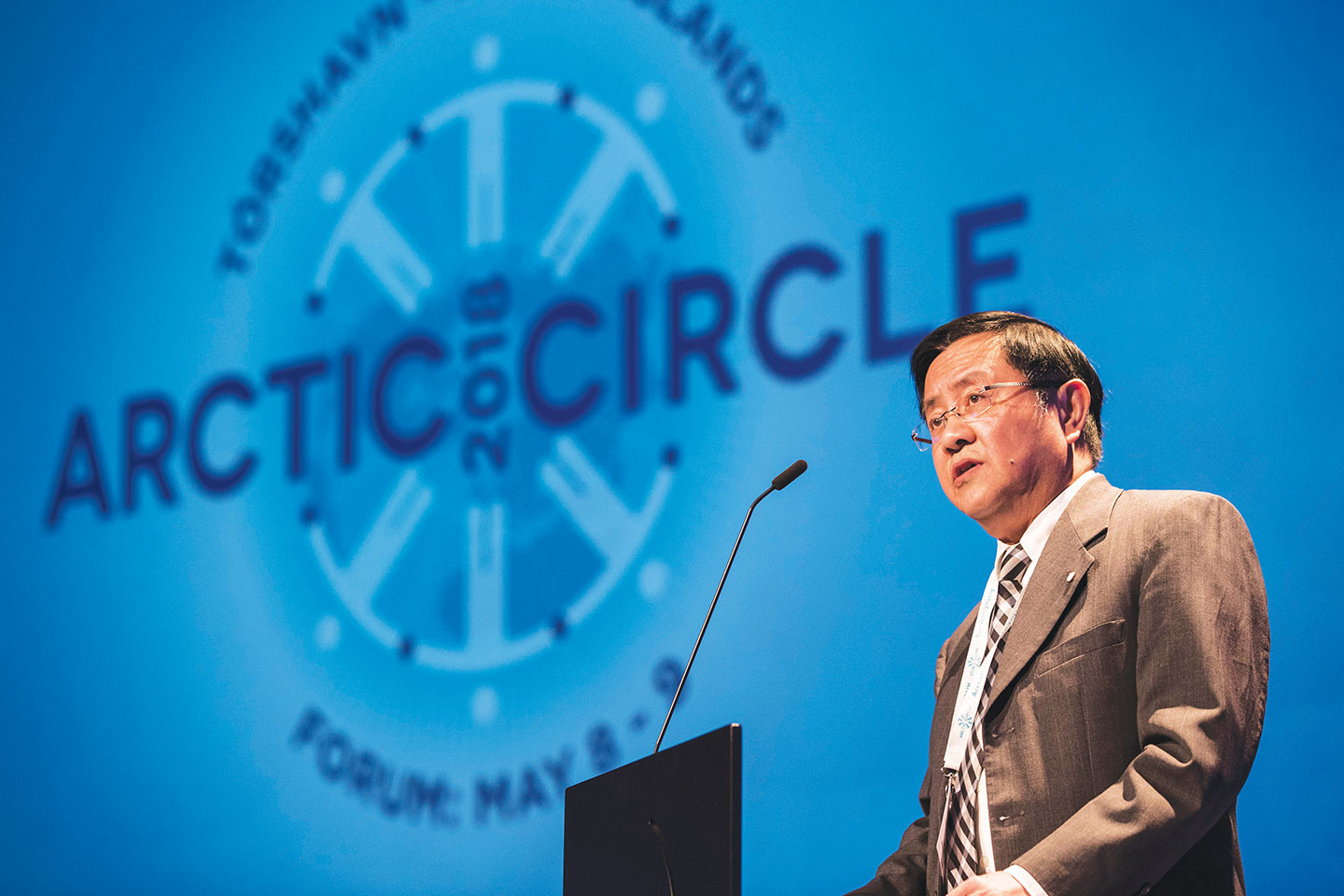

MARC LANTEIGNE/UiT THE ARCTIC UNIVERSITY OF NORWAY

Although the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 did not directly affect the geopolitics of the Arctic, strategic spillover from that conflict into the High North has been easy to detect. With the Arctic now being more directly incorporated into NATO’s strategic interests and with the alliance expanding to include Finland and potentially Sweden, there has been a de facto bifurcation of the Arctic into Western and Russian zones. The Arctic Council remains in near-abeyance, and questions remain about whether any revived cross-regional cooperation will be possible. Norway took over the chairmanship of the group from Russia in May 2023.

As the largest non-Arctic country, and one which has often referred to itself as a near-Arctic state, the People’s Republic of China (PRC) finds itself in a more precarious position in the region as compared to five years ago when it launched its ambitious white paper, which proclaimed Chinese interests in being a key stakeholder in the far north. Beijing’s plans for the Arctic assumed that the region would be open and amenable to the development of three main pillars of Chinese Arctic policy, namely scientific diplomacy, economic partnerships and participation in regional governance initiatives. All three of these pillars are now under pressure, which has underscored the PRC’s limitations in the Arctic and will inevitably force a rethinking and likely a retrenchment of the country’s far-northern interests.

Nonetheless, there remain two widespread assumptions concerning the PRC’s status in the Arctic. These need to be carefully unpacked; namely, that the country’s presence in the Arctic is looming and increasing, and that polar cooperation between the PRC and Russia will inevitably deepen to the point that a formalized Arctic strategic partnership will be created. The events of the past year, however, have called both suppositions into question.

Despite hopes in Beijing that the PRC’s Polar Silk Road initiative would emerge as an integral part of the overall Belt and Road framework, many centerpiece projects of the infrastructure initiative have either failed or are in doubt because of financial constraints, political opposition or some combination thereof. These include, but are not limited to, Chinese investments in the Kuannersuit rare earths and uranium mine and the Isua iron-extraction projects in Greenland; the Kami iron-ore project and the purchase of TMAC Resources, a mineral exploration and development company, both in Canada; and the oft-discussed Arctic Railway project in the Nordic region. Chinese concerns have also been pushed out of plans to construct an undersea fiber-optic cable in the Arctic Ocean. Even before the invasion of Ukraine, the PRC’s maneuvering room in the Arctic was being reduced after Beijing’s diplomatic relations chilled with several Arctic governments, including Canada, Denmark, Sweden and the United States. The PRC’s economic momentum in the Arctic was further stalled by the pandemic, Russian actions in Ukraine, and questions about the near-term health of the Chinese economy.

Concerning Sino-Russian relations in the far north, attention was justifiably paid to the joint statement between Chinese President Xi Jinping and his Russian counterpart, Vladimir Putin, mere weeks before Ukraine was attacked, which affirmed a “no limits” partnership that included “practical cooperation for the sustainable development of the Arctic” and the further opening of regional maritime trade. Beijing has also been an enthusiastic buyer of Russian oil (at discount prices) and has repeatedly deferred from condemning the Ukraine invasion. Yet, a closer look suggests growing Chinese apprehension about a too-close political and economic relationship with Moscow, including in the Arctic. Chinese firms have been sporadic at best in their engagement with the Arctic liquefied natural gas (Arctic LNG-2) project in Siberia, and no China-flagged cargo vessels transited the Northern Sea Route connecting Asia with Europe via the Siberian coast in 2022, reflecting Chinese concerns over being subject to Western sanctions for assisting the Putin regime.

With the PRC’s economy facing domestic travails caused by draconian “zero-COVID” restrictions and the health risks created by their rapid removal late in 2022, as well as external pressures from Sino-American trade competition, a Russia-first diplomatic approach makes less sense. Moreover, with Moscow seeking to augment its Arctic defenses and NATO expanding its own presence in the Nordic region, Beijing will find it much more difficult to engage in both scientific and economic diplomacy to the lengths it envisioned when the white paper was published.

The PRC will not be abandoning the Arctic as a region of strategic concern, but it will be crucial for the United States and others to recognize restraints in Chinese interests in the far north as many governments try to navigate the drastically changed political mosaic of the region.

Comments are closed.