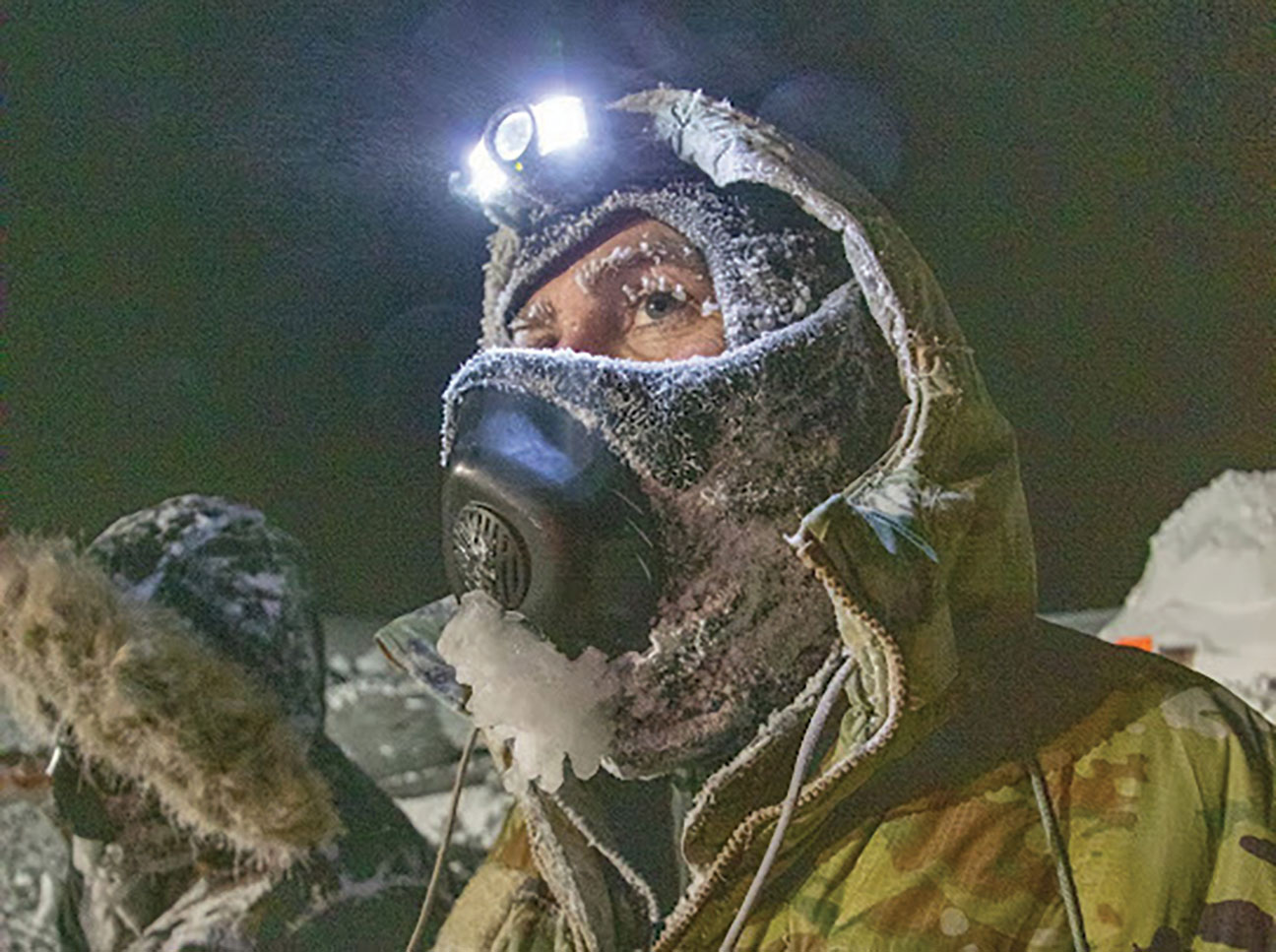

United States Air Force Master Sgt. Cody Hallas of the 133rd Contingency Response Team builds an igloo in Crystal City, Canada, during a field training exercise. The U.S. and Canada’s strong Arctic defense partnership includes bilateral training. 133RD AIRLIFT WING/U.S. AIR FORCE

Canada released its revised Arctic Foreign Policy (CAFP), which supplements its 2019 Arctic and Northern Policy Framework statement’s international chapter, due to profound geostrategic changes that have spilled over into Arctic affairs. Then-Minister of Foreign Affairs Mélanie Joly’s foreword paints a dramatic picture, lamenting that “for many years, Canada has aimed to manage the Arctic and Northern regions cooperatively with other states as a zone of low tension that is free from military competition. … However, the guardrails that we have depended on to prevent and resolve conflict have weakened. Russia’s illegal war in Ukraine has made cooperation with it on Arctic issues exceedingly difficult for the foreseeable future. Uncertainty and unpredictability are creating economic consequences that Canadians are facing every day.”

In the policy released on December 6, 2024, Joly was careful neither to cast the CAFP as the culmination of a new full-scale codevelopment process nor as a full strategy, like Canada’s Indo-Pacific Strategy released in 2022. Instead, the policy reiterates that Canada’s desired end state is “a stable, prosperous and secure Arctic” with “strong and resilient Arctic and Northern communities,” and with Canada’s foreign policy serving to “advance the interests and priorities of Indigenous peoples and northerners who call the Arctic home.” By comparison, the Conservatives’ 2010 Statement on Arctic Foreign Policy set its vision for the Arctic as “a stable, rules-based region with clearly defined boundaries, dynamic economic growth and trade, vibrant Northern communities, and healthy and productive ecosystems.” In this sense, Joly’s statement at the launch of the CAFP heralding “a fundamental change in how we look at the Arctic” is somewhat of an overstatement. Instead, one might see the 2024 statement as a logical continuation of Canada’s Arctic foreign policy since the late 1990s, albeit with a much stronger emphasis on defense and security, and likely to attract support across federal party lines.

Nevertheless, Canada’s evolving policies on Arctic defense and security reflect changes in the geopolitical environment. Canada’s defense policy update, Our North, Strong and Free, released in April 2024, placed an unprecedented focus on the Arctic as the most strategically important region for Canada in contributing to the defense of North America and of NATO’s northern and western flanks. Russia, which was framed as a potential Arctic partner in Canada’s 2019 policy framework, is now clearly acknowledged as a competitor with whom there can be no “business as usual” given its invasion of Ukraine and disregard for sovereignty, territorial integrity and international law. “It is clear that Russia has no red lines,” Joly noted at the CAFP’s December launch in Ottawa, and the “guardrails” that prevent conflict in the region are “increasingly under strain.” This means that “the Arctic is no longer a low-tension region, and to respond to threats from Russia and non-Arctic competitors such as the Chinese Communist Party, Canada must be strong in the North American Arctic, and it requires deeper collaboration with its greatest ally, the United States.”

The key alignments between Canada’s Arctic foreign policy and U.S. strategic documents make this a natural focus. Canada and the U.S. have a shared commitment to maintaining a secure North American homeland. The promise to reopen a Canadian Consulate in Anchorage, Alaska, and another in Nuuk, Greenland, reflects a desire to deepen east-west diplomatic relationships across the North American Arctic. In September 2024, Ottawa announced the launch of maritime boundary negotiations with Washington regarding the Beaufort Sea, opening the opportunity to showcase how good neighbors resolve long-standing legal disputes. Furthermore, Canada’s intention to initiate an Arctic security dialogue among the foreign ministers of the seven like-minded Arctic states dovetails with U.S. designs to strengthen regional defense and security architectures. This new mechanism to strengthen coordination and dialogue with Arctic allies on security issues complements the existing Arctic Chiefs of Defence meetings, Arctic Security Forces Roundtable and other bodies in which key allies share information and improve their collective understanding of circumpolar threats.

“Canada is an Arctic nation, and we are at a critical moment. We live in a tough world, and we need to be tougher in our response,” Joly said at the news conference announcing the CAFP. “I don’t think the Arctic will be the primary theater of conflict. I see the Arctic as the result of what is happening elsewhere in the world.” In short, Canada’s evolving Arctic strategic policies reinforce that Arctic affairs are not insulated from broader geopolitical competition.

The CAFP flags the “continued deepening of Chinese-Russian military cooperation, particularly in the North Pacific approaches to the Arctic,” as worrisome given the desire of both strategic competitors “to undermine the liberal rules-based international system.” Since the Cold War, Canada has traditionally focused on the North Atlantic-Arctic connection, including the Greenland-Iceland-United Kingdom gap, as its primary area of focus. By broadening the aperture to include North Pacific-Arctic interconnections and explicitly recognizing the North Pacific and Bering Strait as another key approach to the North American Arctic, Canada is shifting its mental map. This opens the conceptual space for Canadians to contribute more fully to a defense partnership throughout the North American Arctic and work to deter Russian aggression and respond to China’s desire to enter the Arctic and enhance its regional profile and prestige.