Nations are cooperating in the Arctic, but increasing militarization could put peace at risk

THE WATCH Staff

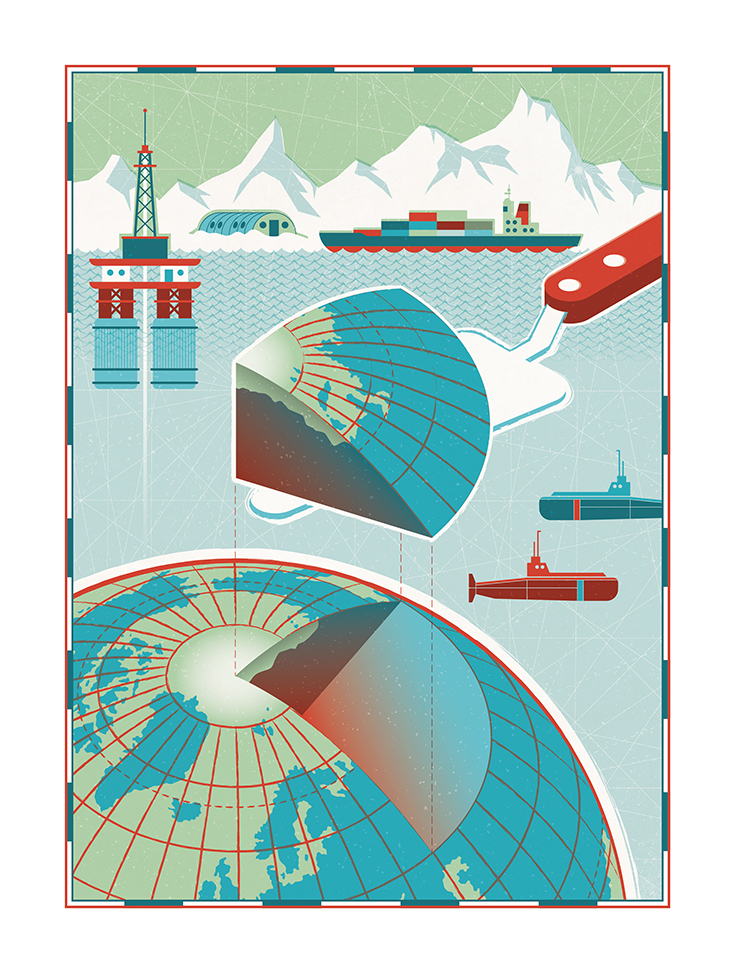

Receding sea ice is ushering in a new resource race in the Arctic. Nations are maneuvering for control of the region, which holds rich deposits of oil, gas and minerals that are becoming newly accessible as the polar ice cap melts at an increasingly rapid rate. The melting ice, which is disappearing at about twice the pace of other spots on the planet, could also open shorter shipping routes between Western Europe and East Asia and expand commercial fishing and tourism opportunities. Some believe the Arctic Ocean will be ice-free during summer months as early as 2020 and year-round by 2050, unlocking potentially more than 20 percent of the world’s petroleum reserves for extraction.

With spoils so alluring, many nations have increased research, exploration, development and other investment in the region as well as militarization, all of which present new quandaries and could threaten regional and global peace and security, some experts say.

“The increased commercial activity brings new challenges, including oil spill prevention, search and rescue, and potentially smuggling and immigration,” says Dr. Michael Byers, an Arctic expert and international relations professor at the University of British Columbia in Canada.

Eight nations have territories in the Arctic — Canada, Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, Russia, Sweden and the United States — but non-Arctic nations are seeking to assert influence in the region.

Russia, Canada and Denmark have formally claimed sovereignty over expanded sections of the Arctic seabed beyond their exclusive economic zones that extend 200 nautical miles from their shores. The overlapping claims, some of which date to before 1925 and include the North Pole, are yet to be resolved under the provisions of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), which governs how disputes over maritime boundaries and territories are resolved and grants countries exclusive rights to harvest minerals and materials from underneath the seafloor of their continental shelves.

Control of the region could also potentially afford strategic military advantages. The U.S. has not made extended claims to the Arctic seabed but is contemplating how to conduct naval surface warfare in the changing Arctic.

Arctic ice ranges up to 5-meters thick in places, making movement difficult. The ice is disappearing more quickly there than anywhere else on the planet, in part, because when the ice melts, the resulting water absorbs heat, speeding warming. Just slightly more than 20 percent of the Arctic’s ice consists of multiyear ice that stays solid year-round, representing a drop of more than 50 percent from 20 years ago, according to the U.S. National Snow and Ice Data Center.

One of the key trade routes opening up, known as the Northern Sea Route, passes through Russian territory, running along its north coast from the Kara Sea to the Bering Strait. Ships can now connect for more days in the year between Russian Arctic ports and Norway. For example, transporting goods from Japan to the Netherlands using this route shaves almost 3,900 nautical miles off the journey via the Suez Canal, according to the Northern Sea Route Information Office in Murmansk, Russia. The other leading route, the Northwest Passage, which runs from the west coast of Canada to Finland, is about 1,000 nautical miles shorter than the conventional route through the Panama Canal.

China has raised its profile in the Arctic in the past decade, given its interest in new commercial routes and increased activities there. China, Japan and South Korea have polar research programs with icebreaker facilities. For example, a Chinese research vessel called the Snow Dragon routinely explores along the U.S. continental shelf. China plans to upgrade its icebreaker fleet and develop technologies for exploiting Arctic natural resources such as deep-water drilling. A Chinese firm has purchased a U.S. $2.35 billion iron ore mining project in Greenland, which is an autonomous territory of Denmark, yet the consortium is awaiting better ore prices to develop it, Reuters reported. The mine has the capacity to produce 15 million tons of ore a year to ship to China.

Arctic Commons

The eight Arctic states created the Arctic Council in 1996 to promote cooperation, coordination and interaction on common Arctic issues such as sustainable development and environmental protection. The council also represents the 4 million-plus inhabitants who live north of 66 degrees latitude, about half of whom are Russian and 500,000 indigenous people.

The Arctic Council has granted observer status to 13 non-Arctic states: China, France, Germany, India, Italy, Japan, Netherlands, Poland, Singapore, South Korea, Spain, Switzerland and the United Kingdom. Another 26 intergovernmental, interparliamentary and nongovernmental organizations, including the newly added World Meteorological Organization and the National Geographic Society, enjoy observer status. The European Union and Turkey have also applied.

On passing the chairmanship from the U.S. to Finland in May 2017, then-U.S. Secretary of State Rex Tillerson said: “The Arctic Council, which recently celebrated its 20th anniversary, has proven to be an indispensable forum in which we can pursue cooperation. I want to affirm that the United States will continue to be an active member in this council. The opportunity to chair the council has only strengthened our commitment to continuing its work in the future.”

Maintaining stability in the region remains critical for protecting economic prospects, experts say. “Military and economic concerns are deeply intertwined in the Arctic,” wrote Stephanie Pezard and several Rand Corp. colleagues in a March 2017 report, “Maintaining Cooperation with Russia.”

“And … these concerns can, at times,” the report said, “lead to apparently disjointed Russian policies in the region.”

More Militarization

Although there seems to be solid cooperation on Arctic Council matters and plenty of commercial opportunities for Arctic nations within uncontested areas of sovereignty where most oil and gas reserves lie, that hasn’t stopped countries from militarizing the region. Russia is leading the military buildup, and most Arctic nations have bases there except Finland and Iceland.

Russia has the most military resources in the region with six military bases, 16 deep-water ports and 13 air bases and is continuing to reopen and build more bases there. In April 2017, Russia unveiled a 36,000-square-kilometer military complex in the Franz Josef Land archipelago called the Arktickhesky Trilistnik, or Arctic Trefoil. It’s designed to protect Russian airspace and other Arctic assets. During its Victory Day Parade in May 2017, Russia showcased two new Arctic missile systems, the Tor-M2DT and Pantsir-SA.

While the U.S.’ interest in the Arctic is more peripheral, “the Russian Arctic is central to the Russian national identity,” Ernie Regehr, senior fellow in Arctic security at The Simons Foundation in Vancouver, Canada, explains. “It has current and potentially much greater importance for the Russian economy, and the northeastern sea route is a major focus of Russian development of the region. The extraordinary Russian icebreaker fleet, its extensive system of search-and-rescue facilities, as well as its formidable military combat capability in the north, all speak to the importance Russia attaches to northern economic and resource development and to its commitment to protecting and advancing its interests there.”

“As I look at what is playing out in the Arctic, it looks eerily familiar to what we’re seeing in the East and South China Sea.”

Adm. Paul Zukunft, then commandant of the U.S. Coast Guard

The increasing militarization of the region is causing concern. Russia is far from reestablishing its Cold War levels of military presence in the Arctic and is not likely to deploy Arctic-based assets in other potential contingencies such as disputes in the Baltic states, according to the findings of the 2017 Rand Corp. report. “Yet increased military presence — not just from Russia but also other Arctic countries — increases risk of collisions and accidental escalation,” Rand’s Pezard concluded.

“The Arctic Council, which focuses on environmental protection and sustainable development, has continued to operate normally despite increased tensions between NATO and Russia. Cooperation on search and rescue is also continuing,” said Byers, who is author of International Law and the Arctic, published in 2013 by Cambridge University Press. “However, communication between the Russian military and other Arctic militaries has broken down, which creates unfortunate risks of misunderstanding and accidental conflict.”

With the ice melting and Russia and China increasing investments and presence in the Arctic, there remains no mechanism to address security issues in the region, including this militarization trend, experts explain. The founding charter of the Arctic Council forbids the body from discussing security matters, leaving it in the hands of individual nations to address military developments through bilateral channels. NATO and Russia do not discuss developments in the Arctic. Without a mechanism, military movements in the Arctic could be misinterpreted or cause a military incident, Heather Conley, senior vice president at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), told The Watch.

Ensuring Cooperation

To be sure, all Arctic nations agree that international cooperation is key for nations to realize the economic potential and ensure prosperity and security of the far north, yet much work remains to achieve such common goals. Finland, as chair of the Arctic Council, aims to focus on the core pillars of the organization, which include enhancing biodiversity, assessing climate change, sustainable development, and protecting the marine environment. Yet some analysts are pushing for stronger mechanisms to resolve security-related issues. “Without predictability, transparency and trust, there will be no international cooperation in the Arctic,” Conley concluded in a 2015 CSIS report titled “The New Ice Curtain: Russia’s Strategic Reach to the Arctic.”

The Simons Foundation’s Regehr agrees. “It is critically important to develop an institution or mechanisms for regular, ongoing consultation on mutual security interests, concerns and enhancements. Whether that can happen within the scope of the Arctic Council is an open question. One huge advantage of bringing security concerns and considerations into the Arctic Council is that indigenous communities would then have a continuing place at the table for security deliberation.”

Ironically, during establishment of the Arctic Council, the U.S. wanted it to avoid military discussions out of concern it would promote militarization of the region. But two decades later, the Arctic is becoming militarized and the international community lacks a forum to discuss security issues. Many experts, including Conley, would like to see the Arctic Council develop a nonbinding political statement to serve as a code of military conduct in the Arctic. For example, such a declaration would mandate that countries notify each other 21 days in advance of military exercises involving 20,000 troops or more and invite observers.

Moreover, Russia’s cooperation in the Arctic should not be taken for granted, according to the Rand report. “If economic ambitions grow increasingly out of reach — for instance, because of low hydrocarbon prices, capital flight and/or the loss of foreign investment and expertise — Russia could have less of an incentive to cooperate and might engage instead in inflammatory actions and rhetoric.”

A disruption of vital resources and routes in the Arctic could trigger military disputes, some experts warn. Additionally, the Arctic Council has opened pathways for foreign influence, especially through investment and expertise. The convergence of territorial disputes, newly emerged commercial shipping lanes and natural resource exploitation could increase tensions in the region, if recent interactions in the South China Sea indicate what’s to come.

Although neither China nor any other country has built and armed artificial islands in the Arctic, territorial disputes could intensify. “As I look at what is playing out in the Arctic, it looks eerily familiar to what we’re seeing in the East and South China Sea,” Adm. Paul Zukunft, then commandant of the U.S. Coast Guard, said at a CSIS-sponsored event in Washington, D.C., in August 2017, according to Defense One, an online security publication.

To avoid any duplication of the gradually escalating tensions in the South China Sea, Zukunft urged the U.S. to ratify the 1982 UNCLOS Treaty, under which the Philippines, for instance, filed suit against China for violating its sovereignty.

The U.S. should also increase its Arctic footprint, he and other analysts assert. “Obviously, we’ve seen what’s happened in the East/South China Sea — even though the U.N. tribunal found in favor of the Philippines, it has not altered the behavior of China,” Zukunft said, Defense One reported. “We can write great policy, but if you do not have presence to exert sovereignty, you are really nothing more than a paper lion,” he told Reuters.

NATO’s Strategic Foresight Analysis report also cautions that mounting resource competition could contribute to instability in the region in future decades.

For now, however, most of the Arctic’s territorial disputes are among NATO allies. And overall militarization of the Arctic has not approached the levels of the Cold War. Moreover, the vast expanses of the Arctic and its extreme weather offer natural defenses to its inhabitants, the University of British Columbia’s Byers says. And little has changed to shorten the great distances between outposts and treacherous climate conditions in the past decade. As Gen. Walter Natynczyk, Canada’s then-chief of the defense staff, said in 2009: “If someone were to invade the Canadian Arctic, my first task would be to rescue them.”