Long-range missile defense system reaches new high

THE WATCH Staff

The Pentagon’s successful test of its ground-based midcourse defense (GMD) anti-missile system on May 30, 2017, could not have come at a more opportune time. Despite global condemnation, North Korea had been accelerating its long-range intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) testing with the stated goal of building a nuclear-tipped weapon capable of striking the United States. Recent test-firings have demonstrated North Korea’s ability to attain its goal sooner than many experts had believed, adding a renewed urgency to developing an effective GMD system.

The missile defense system is part of an array of efforts by the U.S., its allies and partners to deter North Korea from developing nuclear weapons and defend against them. North Korea agreed in the historic June 12, 2018, summit with U.S. President Donald Trump to halt tests and work toward denuclearizing the Korean Peninsula, although experts agree that could take many years to achieve.

“If left on his current trajectory, [North Korean leader Kim Jong Un] will ultimately succeed in fielding a nuclear-armed missile capable of threatening the United States homeland.”

Lt. Gen. Vincent R. Stewart, director of the U.S. Defense Intelligence Agency

The successful test used a sea-based radar system in the Pacific Ocean to track a mock ICBM and feed data into the GMD system. A “kill vehicle” equipped with tracking sensors separated from its missile and, moving at speeds exceeding 6.4 kilometers per second, destroyed the target in space by moving directly into its path. “The intercept of a complex, threat-representative ICBM target is an incredible accomplishment for the GMD system and a critical milestone for this program,” Vice Adm. James D. Syring, director of the U.S. Missile Defense Agency (MDA), said in a prepared statement. “This system is vitally important to the defense of our homeland, and this test demonstrates that we have a capable, credible deterrent against a very real threat.”

THE CHALLENGE

The path to that successful test can be traced to the 1999 National Missile Defense Act, which directed the Pentagon to create a system capable of protecting the U.S. from a long-range ballistic missile attack. Three years later, President George W. Bush called for a workable missile defense system to be in place by 2004. In response, the newly formed MDA developed a land-based missile system to track and intercept ICBMs in space, before descent into the atmosphere.

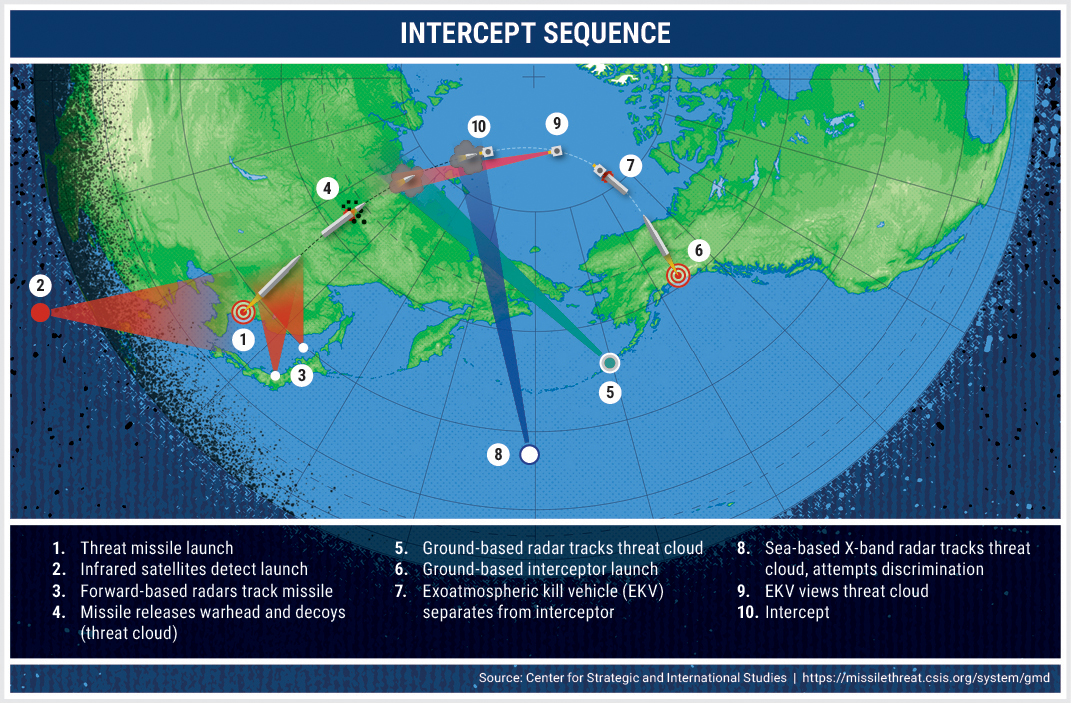

Using land, sea and space radars, the system detects a threat and triggers the launch of a three-stage booster rocket with an interceptor missile. Atop the interceptor is a detachable exoatmospheric kill vehicle (EKV) with onboard sensors and thrusters that set a trajectory for colliding with an incoming warhead. The collision is described as the equivalent of hitting a bullet with a bullet. Fallout from the destroyed ICBM occurs in space, sparing the targeted populations below. The GMD’s long-range targets differentiate the system from the Pentagon’s existing Aegis, Patriot and Terminal High Altitude Area Defense (THAAD) systems, which are designed to respond to medium- and short-range threats.

The MDA housed its interceptor missiles at two sites: a repurposed World War II-era military base in Fort Greely, Alaska, and at Vandenberg Air Force Base in California. Initial testing results showed improvement over several years, including a June 2014 test during which the GMD system destroyed a test target moving in space over the Pacific Ocean.

MAY 30, 2017

Then on May 30, 2017, the intercept of a mock ICBM exceeded all previous tests. The MDA launched an unarmed ICBM from Kwajalein Atoll, prompting the launch of an intercept missile from Vandenberg AFB. Radar in the Pacific Ocean tracked the missile while sensors on an EKV with newly redesigned guidance thrusters calculated the speed and direction needed to intercept the target. The direct collision represented the first successful live-fire GMD test against an ICBM-class target.

The results ignited greater optimism in a program that is seeking nearly U.S. $1 billion for missile defense in 2018, when it expects to have 44 ground-based interceptors in place at Fort Greely and Vandenberg AFB, the most ever in the program’s history. In development is a redesigned EKV that could destroy multiple targets in a single launch, and improved interceptors and sensors. The complexity of the task and the system’s testing history continue to raise concerns among critics. But the success in May 2017 prompted the Pentagon’s Operational Test and Evaluation office to upgrade its GMD assessment to “demonstrated capability to defend the U.S. homeland from a small number of intermediate-range or intercontinental missile threats with simple countermeasures.”

RAISING ALARMS

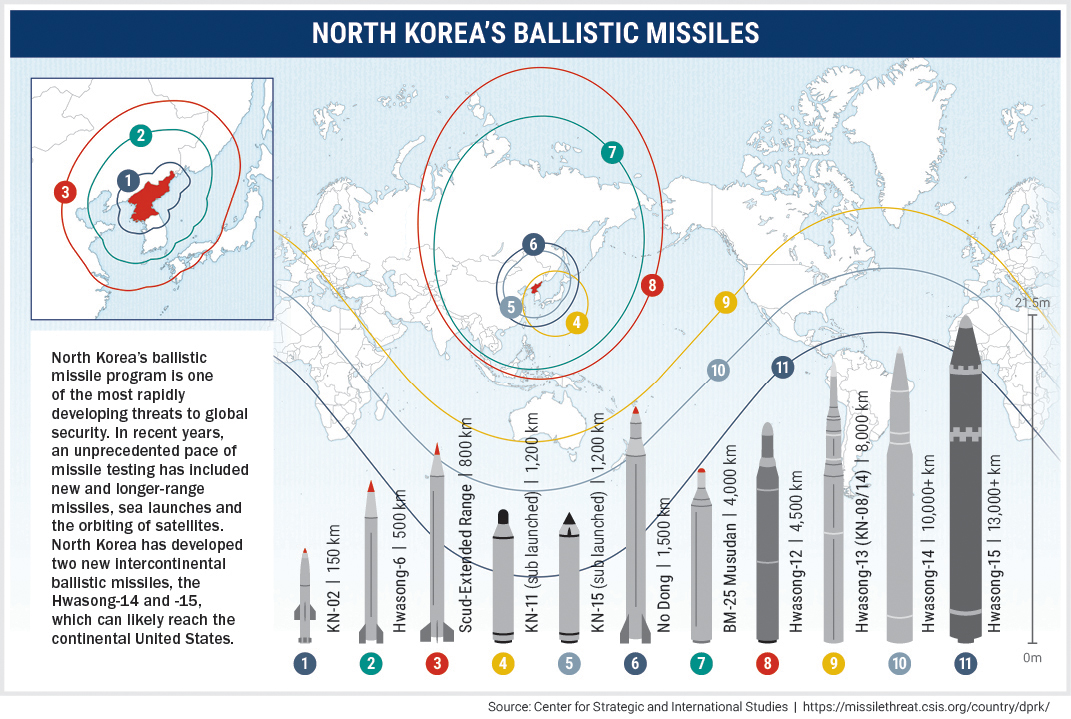

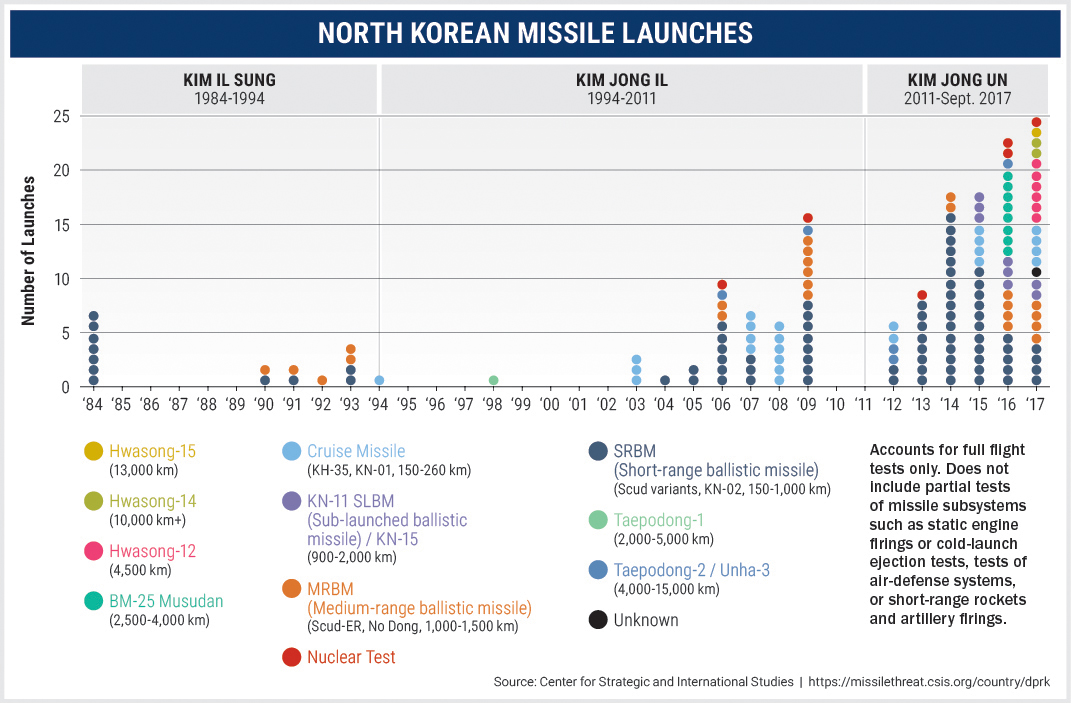

Just weeks after that successful test, North Korea raised the stakes for the U.S. to build and maintain a reliable GMD system. Twice in July 2017 the North Koreans test-fired ICBMs capable of reaching most of the U.S. Several more launches followed before the end of 2017. Based on government assessments, North Korea now possesses the technology to shrink a nuclear weapon to fit atop an ICBM, though it remains uncertain whether that nuclear weapon could withstand re-entry into the atmosphere. Either way, the tests eliminated any doubts about North Korea’s ability to launch ICBMs that can reach the continental U.S.

It’s a goal North Korea has been building toward at an accelerated pace. In 2009 it test-fired a missile in violation of the 1953 Korean cease-fire. Over the past five years, it has flouted United Nations Security Council resolutions by detonating underground nuclear devices and conducting dozens of missile tests, each one raising new alarms. For instance, past missiles were powered by liquid fuels that took hours to load, leaving them exposed to surveillance. Solid fuels now being used allow the North Koreans to move a missile from a secure position and launch within minutes, leaving little time for targeted countries to prepare. Within 10 years North Korea could wield a nuclear arsenal with ICBMs capable of being launched from land, air and sea, some analysts believe. “If left on his current trajectory, [North Korean leader Kim Jong Un] will ultimately succeed in fielding a nuclear-armed missile capable of threatening the United States homeland,” said Lt. Gen. Vincent R. Stewart, director of the U.S. Defense Intelligence Agency.

PROLIFERATION

North Korea isn’t the only country with a global missile system that poses a threat to the U.S. or its interests abroad. Iran’s desire to have a strategic counter to the United States could drive it to field an ICBM. Progress in Iran’s space program could shorten the pathway to an ICBM because space launch vehicles use inherently similar technologies. Russia has an array of ICBMs and cruise missiles, and China is modernizing its ICBMs and developing nuclear ballistic missile submarines. These tallies don’t include more than 6,300 ballistic missiles that are beyond the control of established powers such as the U.S., Russia, China and NATO. In the 1970s only nine countries possessed ballistic missiles. Forty years later, the number exceeds 20, including potentially hostile regimes with ties to terrorist organizations.

That buildup makes missile proliferation among the world’s greatest threats. Countries without ballistic missiles can now acquire them quickly and make them available to terrorist groups. Or North Korea, strapped for cash amid deepening sanctions, might sell surplus nuclear weapons to rogue states. “In light of the strategic threat presented by North Korea, defending the United States against intercontinental ballistic missiles remains USNORTHCOM’s highest priority mission,” Gen. Lori J. Robinson, then commander of U.S. Northern Command, testified before the U.S. Senate Armed Services Committee.

CONCLUSION

Beyond its material benefits, a reliable GMD system affirms the U.S. commitment to protect allies and deter adversaries anywhere in the world. It can deny hostile regimes the political benefits of having a weapon that can be used to threaten or blackmail peaceful nations. It can deter the buildup of nuclear missile systems by making them obsolete.

The U.S. has used economic sanctions and a cyber campaign to disrupt North Korea’s missile system. While those tools have slowed North Korea’s progress and generated attention and international pressure, the North Korean regime has yet to dismantle its nuclear arsenal. “We don’t have to wait until they have an intercontinental ballistic missile with a nuclear weapon on it to say that now [the threat] is manifested completely,” U.S. Defense Secretary James Mattis said.